Recently I located a copy of Tobias Matthay’s book “How do you do Mr. Piano?’ Book 1 at a second-hand book shop in Auckland. It is also entitled ‘The Matthay-Craxton-Swinstead Approach to Music’. It was published in 1940 and cost 3/- to buy in the UK. The book is quite large, uses a large font and contains some lovely illustrations. There is quite a lengthy preface to the book where Tobias Matthay discussed how the teacher is faced with the task of choosing the right music at every particular moment of a pupil’s musical career. He states that the book is not a beginner’s book and that the pupil should have exposure to other books. He discussed the see-saw type of melodic progressions which call for the alternate rotary actions of the forearms. He feels that consecutive progressions are muscularly more difficult for the beginner. Matthay’s belief is that when a pupil commences playing hands together, that it should be in contrary motion because pieces that use similar motion with hands together demands opposite rotative impulses and that this can lead to muscular conflict or ‘stiffening’. He then covers the correct tone production that a pupil should use. However, he feels that above all, the pupil must listen for the rhythmical progression in a phrase, that is towards the phrase-climax, towards the climax of the whole piece, towards each pulse ahead in quick passages, and most important of all, towards tone emission in each key-descent. Matthay mentions two ladies who helped with the compilation of the book, Miss Hilda Dederich and Miss Denis Lassimonne.

When learning the pieces in the book, Matthay recommends that the pupil learns the rhythm first by clapping or tapping it out and also being able to recite the words rhythmically. He states that both hands should be kept on the piano even if one is not being used and that some of the first pieces could be learnt by rote. Following this introduction, there is information concerning the position of notes on the piano, that both thumbs will need to be on middle C and that the pupil should keep their eyes on the music as much as possible.

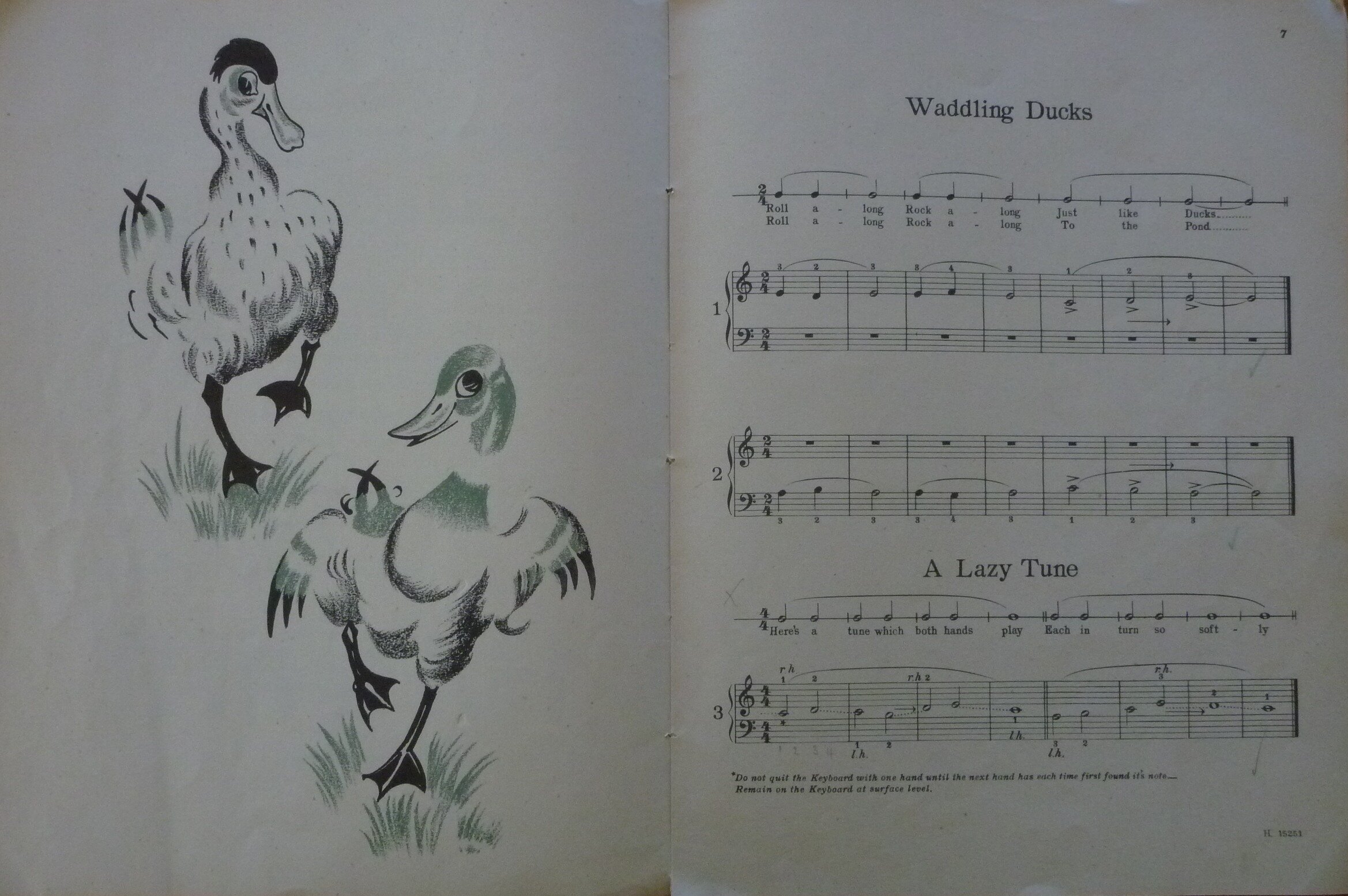

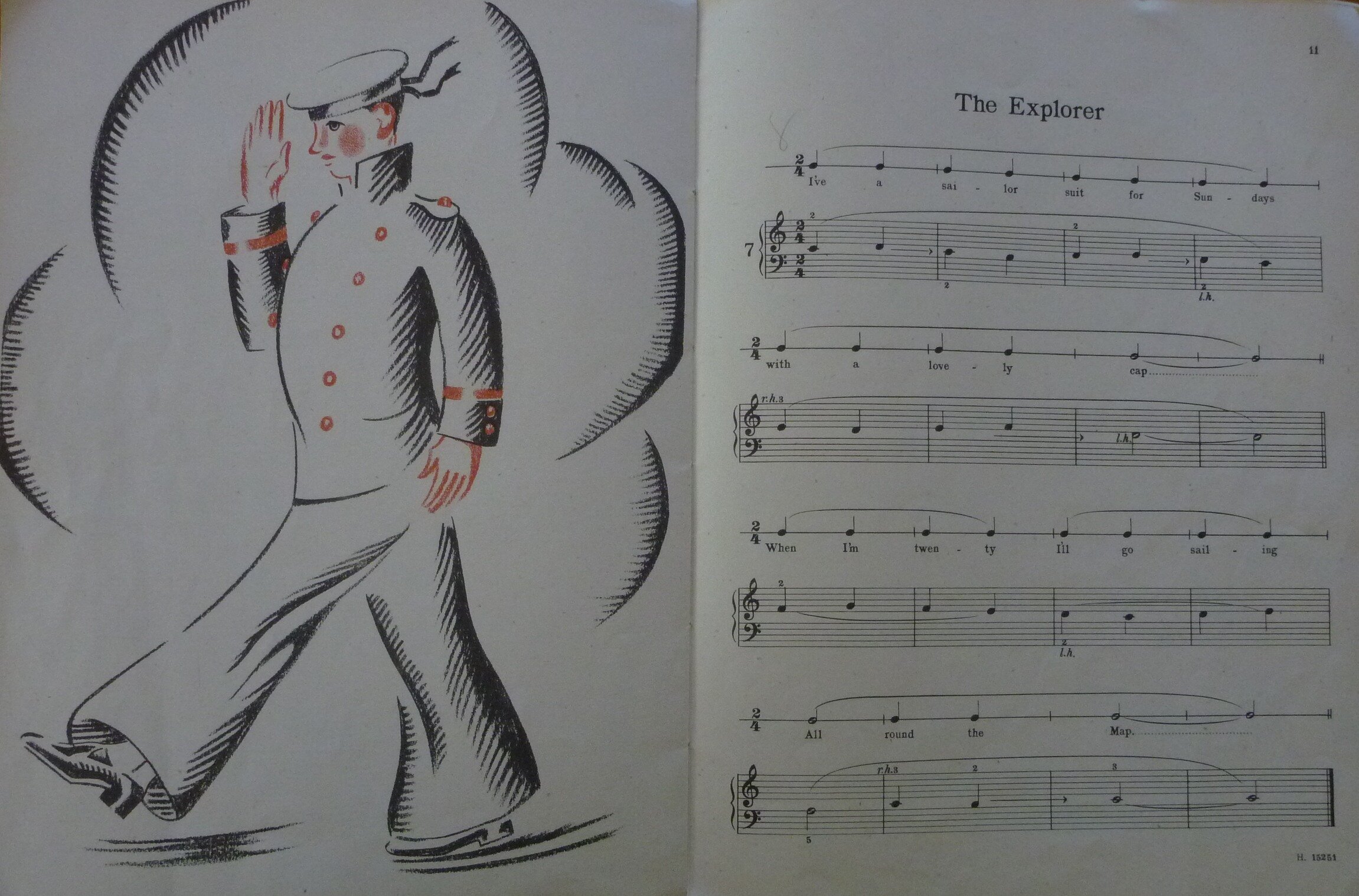

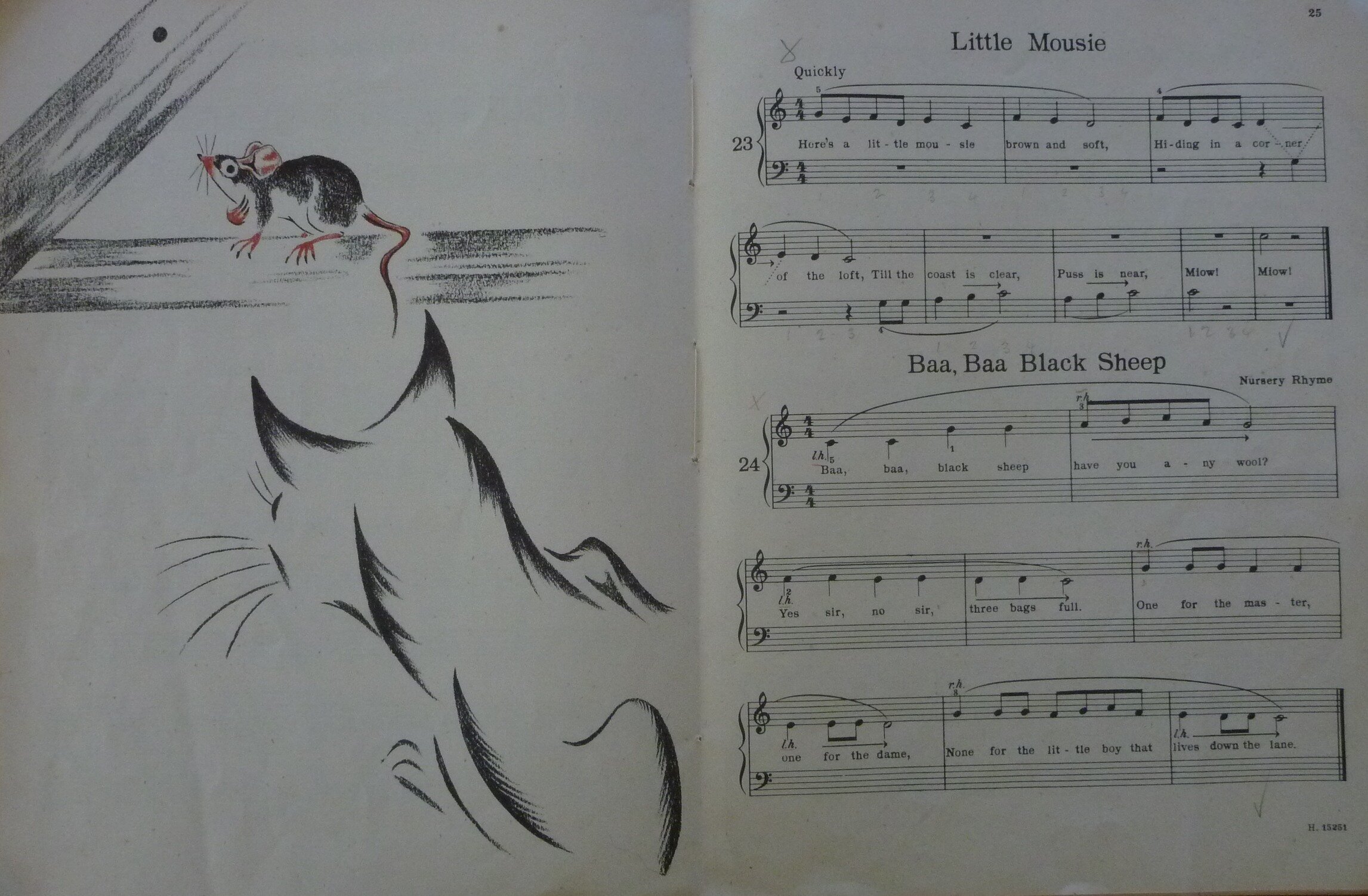

It is interesting to note that the rhythm for each of the pieces is written out separately to the music. There are titles for all of the pieces such as ‘A Lazy Tune’ and ‘My Toy Train’. I notice that the hands overlap at times and that there is not a lot of fingering provided. At times the LH is playing in the treble clef and using ledger line notes. It is ironic to see that a teacher has written next to a piece in triple time ‘don’t lose the rhythm’ and that counting has been written in, in some instances. Later on in the book are familiar pieces such as Pussy Cat, Bonny Bobby Shaftoe and Pease Pudding Hot.

21 Arkwright Road, Hampstead. By Spudgun67 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74932468

By Spudgun67 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74932469

I spent some time researching Tobias’ Matthay’s life and also locating some newspaper articles about him and his wife. Tobias Matthay was born on the 19th February 1858 in Clapham, Surrey to parents Tobias and Dorothy Matthay. His parents were born in Prussia, Germany and both were naturalised British citizens. His father was a Professor of German and French. They are living at 40 Manor Grove, Clapham. In the 1871 Census, Tobias junior has a one year old sister, Dorothea. He entered the Royal Academy of Music in 1871 and won the Sterndale Bennett Scholarship. In 1876 he became a sub-professor and a full professor in 1880. In the 1881 Census, Tobias junior, now aged 23 years old, is listed as a pianist, composer and professor. By the 1891 Census, Tobias junior is listed as a Professor and composer of music. His sister Dorothea is a Teacher of Music. He married Jessie Kennedy, daughter of Scottish singer David Kennedy on the 10th August 1893 at 5 Mayfield Rd, Edinburgh. She became a well-known reciter under her married name. Jessie died in 1937. I cannot locate Tobias Matthay junior in the 1901 Census, however I can locate his wife Jessie and his sister who are living in Croydon. Jessie Matthay is listed as a Teacher of Singing and Dorothea (listed as Dora) Matthay is a Teacher of Pianoforte. In about 1905 Tobias Matthay founded the Tobias Matthay Pianoforte School in London in Oxford St, later Wimpole St and there were other branches of the school in the UK and overseas. The 1911 Census provides more information that previous ones. Tobias Matthay and his wife Jessie, are living at their country home High Marley, Haselmere in Surrey. The house has nine rooms. He is a Professor of Music (Pianoforte), composer, writer and lecturer of music and Jessie is a Professor of Elocution and Singing and both are working at home and elsewhere. Mary Lediard, a music student aged 17 years old is visiting the couple. In 1913, Jessie Matthay donates £1 1s to a suffragette fund.

From Alamy.com

Familysearch have a number of entries for electoral rolls for Tobias Matthay, some of whom could be for his father. In 1911, Tobias Matthay junior is on the roll for 96 Wimpole St, Marylebone. (His parents died within months of each other in 1909). In the 1939 Register Tobias Matthay is living at High Marley with Denise Lasssimonne and Hilda Lindars. All are listed as Professors of Music.

Tobias Matthay died on the 14th December 1945 of a heart attack at High Marley and probate is granted on the 29th March 1946 to Dame Myra Hess O.B.E., Denise Lassimonne both spinsters, Hilda Lindars married woman and Vivian Langrish Professor of Music. In the Times dated 15th April 1946 there is an entry for ‘Wills and Bequests’. He left £18,512 and left a number of personal bequests and the remainder, to the council of the Tobias Matthay Pianoforte School Limited, or if it ceased to exist, the Royal Academy of Music.

The Times on the 24th December 1900 has a column discussing new music that has been published. Two pieces that have been written by Tobias Matthay have been published; ‘one is a “Romanesque” which is graceful and taking, in rather a Lizst-way and “Con imitazione” in which a severer style is copied with a good deal of success’. In another paper, the Western Daily Press in Bristol describes a concert given by a Miss Nan Dove. One of the pieces that she played was a set of Tobias Matthay’s Variations, opus 28 which according to the article, ‘are a series of studies in virtuosity, making great demands upon the technical skill of the performer. She grappled with these difficulties, but also managed to work out some phrasing that made the work intelligible to those hearing the work for the first time’.

There is an interesting article in the Times dated 1st March 1909 concerning a reception in the ‘Honour of M. Debussy’. Mr Tobias Matthay was one of those present. Debussy was welcomed in his own language and he replied briefly to the compliment paid to him. The concert was devoted to Debussy’s compositions.

In the Daily Mail dated 25th July 1925 there is an article headed R.A.M. dispute, Piano Teacher resigns. According to the article, Tobias Matthay had serious differences of opinion with the principal of the R.A.M. Mr John B. McEwen. Mr Matthay had been with the Academy for 54 years. He told the reporter that there have been numerous points which he disagreed with the principal and he felt that he could not continue in such an atmosphere. The disagreements were about Mr Matthay’s method of conducting pianoforte classes. It was said the Mr McEwan suggested that Mr Matthay should have more pupils under his tuition at one time.

In an article written in the Times dated 19th February 1943, the writer discusses the legacy of Tobias Matthay’s piano teaching. The article discusses that his piano books for children aim ‘to make music, that is, to produce the right sound, before the young mind is diverted to tackle other intellectual problems’.

Tobias Matthay. Illuminated testimonial in the form of an encased triptych on parchment. From Alamy.com

In the Times on the 12th June 1958 there is an account of a commemoration for Tobias Matthay. He was born 100 years before and it states that he taught at the Royal Academy of Music for many years. It goes on to say that his legacy mostly is in his teaching and he became known as the master of the ‘art of touch’. The writer of the article states that Tobias Matthay’s writing is often considered ‘formidably turgid’. Also, it states ‘that his doctrines were the subject of controversy in his lifetime but his positive contribution to the musical life of the country abides’.